A Miracle Cure for Addiction?

Ocean Drive

by Tristram Korten

Photographs © 2006, Simon Hare Photography

Ocean Drive Magazine / (April 2006)

Though South Beach may be a hotspot for A-list substance abuse, across the causeway a Miami doctor is struggling to legalize an astonishing treatment derived from an African plant.

Though South Beach may be a hotspot for A-list substance abuse, across the causeway a Miami doctor is struggling to legalize an astonishing treatment derived from an African plant.

Most people would find it counterintuitive that Miami, the land of the pleasure ethos, of models and VIP parties, could offer anything healthy to a junkie. The nightlife here alone has probably seduced more people into an addiction of one kind or another than most other American cities.

But in 1999, Patrick Kroupa, a pioneering and wildly successful computer maverick, was interested in a different Miami. The days when he could have enjoyed all that South Beach had to offer were long gone. “I shot it all up,” he says, laughing.

The Miami Kroupa was after lay in a research lab in the middle of the city. That’s where Dr. Deborah Mash, a University of Miami neurologist, had been studying the effects an African plant named ibogaine had on addicts.

The Miami Kroupa was after lay in a research lab in the middle of the city. That’s where Dr. Deborah Mash, a University of Miami neurologist, had been studying the effects an African plant named ibogaine had on addicts.

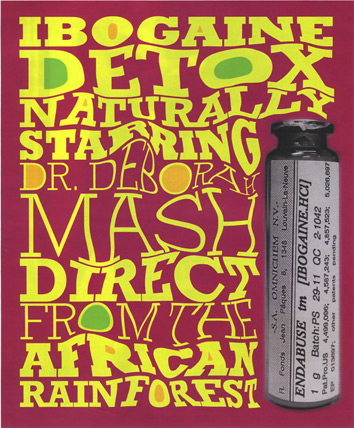

Mash believed that ibogaine, which is extracted from the root of the West African shrub Tabernanthe iboga, could interrupt the brain’s dependence on opiates, cocaine and alcohol. She was trying to determine the exact reason why and had some initial government sanction. To help fund her study, with the ultimate motive of seeking approval to make it widely available, she established a clinic on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts. At the clinic, addicts of last resort were treated with controlled dosages of ibogaine in a medical setting. The drug was, and remains, classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration as a Schedule 1 substance, illegal to possess or administer in the United States except by special license.

In October 1999, Kroupa was able to round up the necessary cash and flew down to St. Kitts. When he arrived, he hadn’t used in about 12 hours and was in the throes of withdrawal – cramping, cold sweats. “My spine felt like it was being crushed,” he says.

In October 1999, Kroupa was able to round up the necessary cash and flew down to St. Kitts. When he arrived, he hadn’t used in about 12 hours and was in the throes of withdrawal – cramping, cold sweats. “My spine felt like it was being crushed,” he says.

Like all such addicts, Kroupa’s body had ceased producing endorphins, a natural opiate that acts as the body’s painkillers. Heroin had taken over that role. When he quit using drugs, his body was left without painkillers and became hypersensitive to stimuli. The end result is constant debilitating agony.

Kroupa’s treatment consisted of wearing a blindfold on a bed in a darkened room, listening to soothing music through earphones, and ingesting about 12 milligrams per kilogram of body-weight of ibogaine hydrochloride in capsule form, while attached to a bank of machines that monitored heart rate, blood pressure and other bodily functions. An IV line was inserted in case he needed to be shot with emergency drugs immediately.

“Within 30 to 35 minutes, this ball of heat went up my spine and the pain just let go,” Kroupa recounts, “Nothing has ever done that. It was like my habit was a bad dream, a mirage. And before I could focus on what had happened I started tripping. Eight and a half hours later they took the blinds off.”

Kroupa says he felt cured. He no longer craved heroin. But it didn’t change 16 years of behavioral patterns and issues (Kroupa is bipolar) that led him to use heroin in the first place. On his way back to the US., his plane stopped over in Puerto Rico, and Kroupa promptly jumped out and copped a bag of heroin. A little more than a month later, strung out again, he returned to St. Kitts for another treatment. This time he followed it up with a stint in a Buddhist monastery.

“That was six years ago,” he says, sipping a Diet Coke at Segafredo on Lincoln Road. He hasn’t used since. Ibogaine changed his life so profoundly that Kroupa signed on to work for Dr. Mash, assisting in clinical studies and managing her databases.

For the past two decades, addicts, activists and a range of physicians and scientists have marveled at ibogaine’s ability to “create a cessation of craving,” as Dr. Mash puts it, in people suffering addiction to a range of drugs, from opiates such as heroin and oxycodone to cocaine, crack and alcohol. For people in the field of addiction science the discovery of ibogaine’s effects is nothing short of groundbreaking – on the level, perhaps, of the discovery of penicillin for treating infections.

For the past two decades, addicts, activists and a range of physicians and scientists have marveled at ibogaine’s ability to “create a cessation of craving,” as Dr. Mash puts it, in people suffering addiction to a range of drugs, from opiates such as heroin and oxycodone to cocaine, crack and alcohol. For people in the field of addiction science the discovery of ibogaine’s effects is nothing short of groundbreaking – on the level, perhaps, of the discovery of penicillin for treating infections.

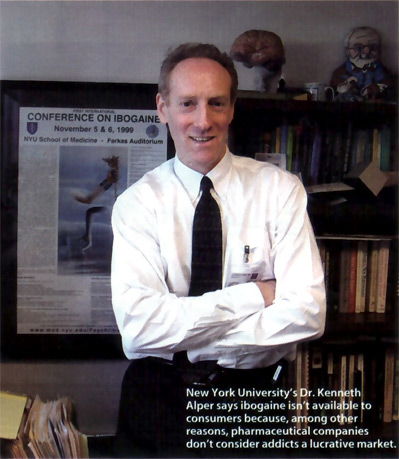

“This is one of the biggest paradigm shifts regarding treatment for addiction in the span of my career,” says Dr. Kenneth Alper, a neuropsychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and neurology at New York University, who has studied and written about ibogaine.

Or, as Miami Beach-based addiction specialist Dr. Jeffrey Kamlet puts it: “In my opinion, this is one of the most important discoveries in the history of addiction medicine.” Kamlet is in a position to know. He has treated dozens of clients with ibogaine in St. Kitts, from nearly homeless heroin addicts to movie actors, popular musicians and successful business people who have abused everything from alcohol to opiate-based painkillers. “Addiction is a non-discriminating disease,” he says. “Just as many, if not more, wealthy, high-end people are addicted, but you don’t necessarily see that because they have the money for lawyers and special treatment facilities.”

Ibogaine’s therapeutic use among movie stars was so prevalent that the supermarket tabloid Star contacted Kamlet a few years ago trying to dig up information. “The reporter told me, ‘I hear you’re treating a lot of movie stars. I’ll give you $500 a name,'” Kamlet recounts. “I told him that was unethical, not to mention illegal, and I wouldn’t do it. Well, the reporter called my secretary and made the same offer! Of course she told me right away.”

Star’s interest (the article that came out was titled “Rare Root Has Celebs Buzzing”) was an indication not only of ibogaine’s growing popularity, but also of the substance-abuse problem among the elite. Heroin use has regularly shown up in the modeling industry and among rock musicians.

“If ibogaine existed when I was a heroin addict, I’d have a completely different life today. I wasted five or six years,” asserts developer and nightlife impresario Michael Capponi. “I went to 12 different rehab centers and spent four or five months on the street homeless. I was on methadone. The whole process was an absolute nightmare.”

“If ibogaine existed when I was a heroin addict, I’d have a completely different life today. I wasted five or six years,” asserts developer and nightlife impresario Michael Capponi. “I went to 12 different rehab centers and spent four or five months on the street homeless. I was on methadone. The whole process was an absolute nightmare.”

And while the heroin scene in club-land is a shadow of what it was 10 years ago when Capponi was hooked, prescription painkillers such as OxyContin and Percocet seem to have taken its place. “Everybody is on prescription painkillers,” Capponi notes. “It goes from people who started taking them for knee surgery and never got off to people who like to take one with vodka and go to a club.”

Indeed, because people come into contact with these powerful new drugs medically as well as recreationally, their use is rampant. Before checking himself in for treatment, right-wing radio host and Palm Beach County resident Rush Limbaugh confessed he became addicted to painkillers after a spinal operation. That mirrors the experience of one Miami businessman, whose use of prescription opiate painkillers also started after back problems. “I had a more-than-two-year addiction to Percocet,” says the middle-aged man, who does not want his name used. At stake was the entertainment company he had built over the years. “The desire was to wake up every day and get enough of that medication to sustain the habit without doing anything illegal and without doing anything that would ruin my business. There were a lot of visits to doctors’ offices and pharmacies.”

While it’s not public what treatment center Limbaugh checked himself into, the Miami businessman eventually found Dr. Mash and flew to St. Kitts to take ibogaine, “I had no withdrawals and no shakes,” he says. “I felt like my brain was rewired. It definitely made me believe in medical miracles.”

University of Miami, Department of Neurology Labs

Scientists are still determining exactly how the substance works. It’s believed to break down into a metabolite whose molecules fit into the brain’s opiate receptors like a key into a lock, literally blocking desire. The metabolite can linger for months. This is believed to provide the other remarkable benefit: Ibogaine is credited with preventing post-acute withdrawal syndrome, the extremely painful weaning process that is the most significant stumbling block for any addict to overcome.

And yet the reality is that ibogaine is unlikely to be marketed as a medical miracle any time soon. That’s because the unique circumstances surrounding the substance have conspired to put it in medical and commercial limbo.

Ibogaine is extracted from a plant, and a plant’s molecular structure can’t be patented. That makes ibogaine an undesirable investment for pharmaceutical companies, the only entities with pockets deep enough to spend the approximately $300 million necessary to shepherd the drug through the clinical trials required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Complicating matters is that some early patents taken out in the 1980s on ancillary aspects of ibogaine have either expired or are about to expire, at which point they will become part of the public domain. “For the pharmaceutical companies, it’s not on their radar,” Alper says. “You can’t expect them to take an interest in a compound that’s going to lose money.”

Still, with an estimated one million heroin addicts nationally, twice that number addicted to prescription opiates, and another estimated two million cocaine abusers, not to mention legions of alcoholics, you would think that some enterprising drug company would be interested in figuring out how to turn a buck with this substance. But the experts say that’s not the case. Apparently addicts are not a desirable demographic.

“There’s the perception that it’s not a lucrative market to serve,” Alper says, because users are engaged in an illegal act, are prone to premature death and might not have the means to pay for treatment. “But that’s not the case.” Studies have shown that most addicts are employed and have insurance.

Then there’s the stigma of working with a psychedelic drug. “The pharmaceutical giants in the world today aren’t interested in looking at hallucinogens as therapeutic entities,” concedes Dr. Frank Vocci, director of the division of pharmacotherapies and medical consequences of drug abuse at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDA reviews applications for new addiction treatments. “The bias is that many people, even scientists, believe that hallucinogens are bad for you and nothing good can come from them,” Vocci says.

Call it the drug culture’s boomerang effect: Serious scientists may believe that working with a “hippie” drug will compromise their reputation. That, of course, doesn’t mean the compounds don’t hold medical value. As far back as the 1950s, scientists were exploring, with some success, the use of LSD to treat alcoholism. MDMA (ecstasy) was first used to treat the chronically depressed. And of course a nationwide debate continues to rage over the medicinal use of marijuana.

That said, there is pragmatism behind the regulatory system that has evolved. “People complain we have this expensive drug-development process,” Alper says. “But on the other hand, it’s relatively rigorous regarding dangerous side effects.”

And there are concerns about ibogaine beyond the vivid visions it provokes. In heavy dosages it can affect the heart, and at least four people around the world have died in unregulated clinics after being treated with ibogaine, although what role it played in their deaths is not always conclusive. Last month, for example, a man attempting to detoxify with ibogaine died at a clinic in Tijuana, Mexico. The cause of death may have involved a prior existing condition.

The deaths highlight what researchers have been emphasizing- that government approval of ibogaine is necessary to prevent unsupervised, clandestine operations from flourishing. Scientific advocates often bring up the analogy of back-alley abortion clinics in the pre-Roe vs. Wade days.

On the fourth floor of the National Parkinson Foundation, a generic red-brick building near Jackson Memorial Hospital, is the NPF’s Brain Endowment Bank, jointly run with the University of Miami. Lining the walls of the bank’s narrow hallways are poster-size medical abstracts with titles such as “Offshore Investigations of the Non-Addictive Plant Alkaloid Ibogaine: 1996-2004” and “Functional Studies of the Dopamine Transporter in Post Mortem Human Brain.” Researchers at the brain bank are as likely to be conversing in Mandarin Chinese as in English.

This is where Mash, a petite, voluble scientist and the bank’s director, conducts her research. Mash has been studying drugs and their effects on humans for two decades. She made a name for herself in 1991 after discovering that a highly toxic compound, cocaethylene, is produced by the liver when people drink alcohol and use cocaine at the same time.

But her current passion is ibogaine.

“Right now ibogaine is my hobby. I’m just doing it on the side,” says Mash, wearing a dark pantsuit and seated in a utilitarian conference room carpeted in industrial brown. She talks in quick bursts of clinically precise sentences and sits perched on the edge of her seat, a veritable coil of kinetic energy. “That’s because we’ve never been able to get the necessary funding.”

“Hobby” does not do credit to the time and energy she has expended on the drug. She runs studies and writes grant proposals. Failing to get the money and acceptance needed to treat patients with ibogaine, she set up the offshore clinic. She did this because, scientifically speaking, she is convinced ibogaine is a “slam-dunk” treatment for opiates, and it frustrates her that it is not available in this country.

There have been some optimistic developments. Mash discovered noribogaine, the metabolite ibogaine produces after it enters the body. Mash believes noribogaine blocks the brain’s opiate receptors. And because noribogaine is stored in body fat and releases slowly over time, its effects continue for up to 90 days.

Mash has received patents for the use of noribogaine and now hopes to attract investors. “My fantasy,” she explains, “is to obtain a joint venture with a pharmaceutical company to develop the metabolite.” She envisions a treatment scenario in which a patient would be able to take an “ibogaine journey one or two times in a clinical setting and then wear a patch containing the metabolite,” she says, much like smokers wear a nicotine patch.

Based on research from St. Kitts, the FDA has approved human trials here in the United States. Mash must now decide if she wants to continue studying ibogaine or simply focus on noribogaine. And, of course, she’ll need money. Some initial funds have come in from donors who wish to remain anonymous. As Mash will tell you, it’s a start. But there have been many starts in ibogaine’s circuitous history, and progress never seems to materialize.

The man credited with discovering ibogaine’s anti-addiction properties is Howard Lotsof. In 1962, Lotsof was a 19-year-old drug enthusiast and heroin user in New York City. His discovery was a serendipitous side effect to his experimentation: “We were not looking for a cure for heroin addiction or cocaine abuse. I was interested in psychoactive compounds and established a research laboratory, S&L Laboratories, to procure drugs and administer them to interested persons,” Lotsof wrote in the underground magazine Overthrow, excerpted in Alper’s academic paper “A Contemporary History of Ibogaine.”

Lotsof gave the drug to 20 people, seven of whom suffered heroin dependence. All seven reported that after one dose their cravings disappeared.

Lotsof took up the ibogaine cause. He studied it and formed a nonprofit organization, the Dora Weiner Foundation, to promote its use. When that didn’t garner the attention necessary to raise money, he formed a for-profit corporation, NDA International, and in 1983 filed patents on the use of ibogaine to treat dependence. But he was never able to secure the funding necessary to bring ibogaine into mainstream use. In 1991 he partnered with the advocacy group International Coalition for Addict Self-Help in the Netherlands, which set about treating patients with ibogaine. Whatever momentum the movement was gaining nearly stopped cold when a patient at the Amsterdam clinic died in early 1993. News stories state the cause of death was inconclusive. But Mash, who had been visiting the clinic, has stated publicly the cause of death was accidental overdose.

It was enough to put a chill on proceedings in the Netherlands and in the U.S., where NIDA was monitoring events.

But Lotsof’s aggressive salesmanship did help seed interest. His company, NDA, contracted with Dr. Stanley Glick at Albany Medical College in upstate New York to run studies. Glick’s tests on animals supported the growing body of evidence regarding ibogaine’s success treating opiate dependency.

Mash, meanwhile, first heard about ibogaine in 1991. She had just finished a lecture sponsored by The Partnership for a Drug-Free America at UM’s Coral Gables campus when a man approached and asked if she knew about an African plant used to treat addiction. “To be honest, I was rude to him,” Mash recounts. “I said, ‘No, I don’t.'” Shortly after that she was at a medical conference and heard Glick give a talk about ibogaine. She was impressed. “I became curious,” Mash says. “I wanted to know how this worked on a molecular level.”

Mash collaborated with Lotsof, traveling to the Netherlands to observe operations in the clinic there. In fact, Lotsof signed a partnership agreement with the University of Miami to further ibogaine studies in the States. In 1993 the FDA gave Mash permission to test ibogaine on humans in the U.s., but only on subjects who had already used the substance.

After initiating the project, Mash deemed it too impractical. The subjects were difficult to locate, let alone round up. “I went back with more data and the FDA gave a full green light” to conduct a “Phase 1 safety and pharmacokinetic test on cocaine-dependent volunteers,” she says, repeating for emphasis “a full green light.” Then she continues: “Well, I tried to fund it, and the bottom line is that grant, and every grant proposal I’ve written for ibogaine, was rejected by the institute [NIDA].”

Pharmaceutical companies underwrite the majority of studies. NIDA provides money for studies on a smaller scale. But the scientists NIDA recruited to review the application had concerns about ibogaine’s safety.

Frustrated that she had permission from the FDA to clinically test ibogaine on humans but couldn’t afford it, Mash found some investors and negotiated with the island of St. Kitts to bring the drug into the country for clinical trials and treatment in 1996.

By this time, Mash and Lotsof’s partnership had devolved into lawsuits, with Mash claiming that Lotsof was trying to control the discovery of noribogaine and Lotsof countering that the St. Kitts clinic violated his agreement with her. The two have since severed their relationship. Lotsof now says that he has quit the regulatory game and focuses his efforts on a patient’s-bill-of-rights endeavor that would legally guarantee ibogaine as an option for recovering addicts.

When the Healing Visions Institute for Addiction Recovery opened, it served a dual purpose, Mash says. Patients signed waivers so their data could be used to further her studies of ibogaine, while addicts desperate to quit their habits were relieved. “Many of these people were chronic relapsers,” she notes.

By 2005, Mash had amassed all the data she needed to go to the FDA. She closed Healing Visions, which, with its costly equipment, always struggled with money. “This was never run for profit,” she says. “It was always for research and development.”

That shuttered one of the few professionally run ibogaine clinics in the world. And for suffering addicts that continues to be a problem.

Even as Mash struggles to win ibogaine’s mainstream acceptance, a blooming subculture of addict self-help groups thrives worldwide as word spreads.

“The underground availability is exploding,” says ex-addict Kroupa, who saw membership in MindVox’s online ibogaine forum grow from 300 to 7,000 in six years. “It’s no closer to any accepted use than it was back when I took it, but in any big city in the U.S. you can always find someone who will treat you.”

This, of course, is exactly what Mash and other scientists don’t want. With unregulated use there is more likelihood of complications, even deaths, which will set back efforts to make the treatment legal. Yet Mash understands. “It’s going underground because people are desperate,” she sighs. And just as quickly, a flash of temper crosses her face: “But that’s going to flush all this effort down the toilet. The point is, this works, but we’ll never be able to show that because hallucinogens have this damaged reputation. Look at the cost of substance abuse. Look at the prisons. Look at lost wages, lost taxes, lost revenues. Look at the violence, the spousal violence, HIV-AIDS, hepatitis C, cardiac problems.”

She pauses for breath. “Nobody in our government is willing to take a risk on ibogaine. And I have to say, maybe we don’t want to solve the problem.”

Pingback: The Unique Scientific Value of Ibogaine, Part 2 | Faith Seeking Understanding